Silent Hill f is poised to be one of, if not the most polarizing entry in Konami’s beloved survival horror franchise. And no, it’s not because the combat is bad. Rather, it’s the twisted, confounding nature of its story. What’s real, and what’s just in Hinako’s head? Did her friends really die? Was marriage really the entire point of this story?

Well, as you may have gleaned from the title, no, Silent Hill f isn’t just about marriage. It certainly uses marriage as a key driving force for its narrative, but it’s more of a backdrop against which we can study all of the other themes that Silent Hill f attempts (to varying degrees of success) to explore.

Marriage Is Death

Even from its first hour, Silent Hill f makes it abundantly clear what marriage means to Hinako. Much of Hinako’s personality is expressed through her journal entries and the way she talks about Junko is especially striking.

Junko used to be the only one she could talk to and confide in. They were thick as thieves from all accounts. That is, until she got married. Even the way that message is delivered is strange. The dramatic breaks in the lines in her journal suggests that Hinako is about to share something dreadful that happened to her sister, like she’s dead or something. But no, she’s just married.

All throughout the confusing and delirious first playthrough, we get brief glimpses of strange conversations between Hinako’s friends, Shu and Rinko, as well. Rinko is constantly telling Shu to forget about Hinako because she’s dead, which doesn’t make sense right? After all, you’re playing as Hinako and you’re interacting with them. It’s all very confusing, until you realize that Rinko isn’t being literal.

There’s a lot of confusion surrounding what’s real and what isn’t in Silent Hill f. I’m of the opinion that most of what happens in-game is actually just an internal battle within Hinako’s head, or at the very least, a horrific overexaggeration of what’s happening to her in real life. I don’t believe that everything is imagined; the fox rituals and godly battles are certainly real, but much of the story wouldn’t make sense if there wasn’t at least some portion of it that just took place in Hinako’s head.

This would explain a lot of things, such as her friends’ overly harsh words towards her, as well as how their words are a reflection of how Hinako actually feels. Since Hinako thinks getting married is the equivalent of dying, then it makes sense that Rinko would describe her as a dead girl.

After all, Hinako is set to get married to a man that her parents have deemed worthy for her. Based on her own experiences with her father (more on that later) and how she perceives Junko, it makes sense to think of herself as dead when she gets married. And if everything is happening in her head, then it makes sense that her own projection of Rinko would say she’s dead, too.

Textbook Objectification: Hinako or Shimizu Hinako?

A big hint that Silent Hill f drops on the player comes in the form of the doll. Towards the end of the game, as Hinako succumbs to the fox’s ritual, the doll tells her to remember that she is Shimizu Hinako. Note that Kotoyuki never refers to her as Shimizu Hinako, and simply calls her Hinako. I believe this is deliberate.

Shimizu serves as Hinako’s family name, but once she gets married, the name Shimizu will no longer be relevant. This is why Kotoyuki never makes mention of the name Shimizu and instead refers to her as “my Hinako”. Similarly, this is why the doll keeps calling her Shimizu Hinako. And it’s also why Hinako insists that she is Shimizu Hinako in her moments of autonomy and rebellion.

The idea of Shimizu Hinako is literally portrayed through the fox’s rituals, where Hinako is forced to give up parts of her body to Kotoyuki and the Tsuneki clan as she gets ready to marry him. By the end of it all, she becomes a completely unrecognizable monster. It’s fitting, then, that in the Fox’s Wedding ending, we see Shimizu Hinako’s face on the floor screaming that she’s scared and doesn’t want to become like her mother.

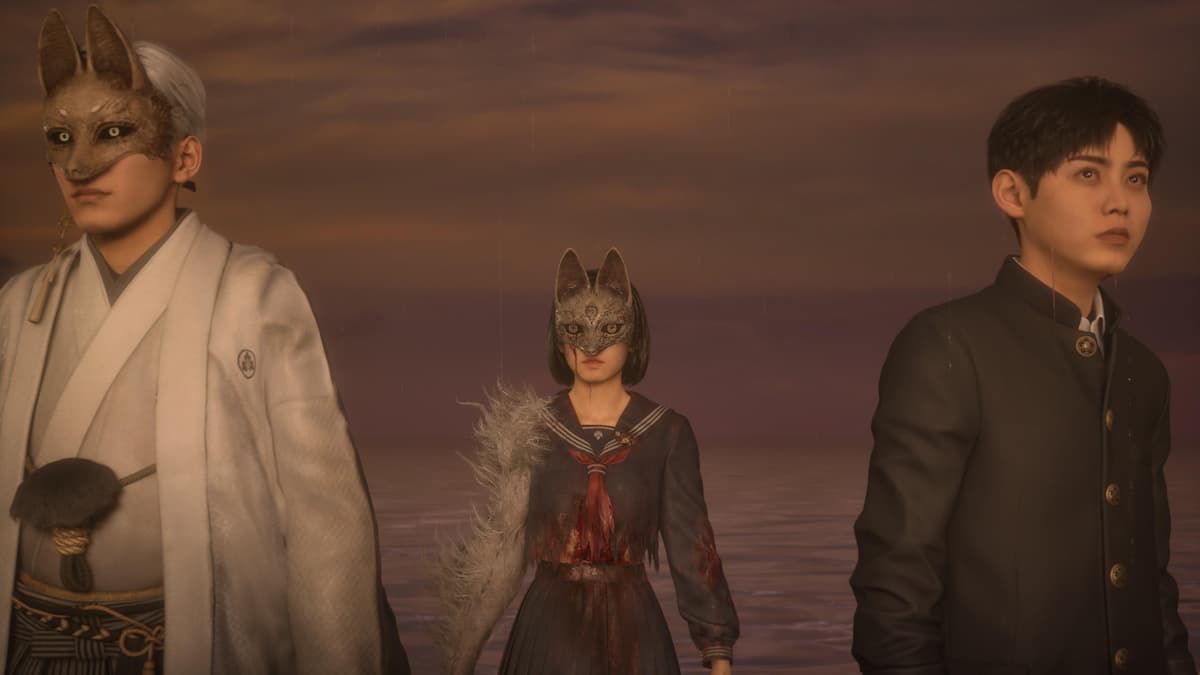

While I don’t believe that Hinako literally cut off her face to become assimilated into the fox’s clan (though this is honestly debatable), it’s fitting that Silent Hill f uses the face imagery to portray the representation of Shimizu Hinako and her loss of identity. It’s meant to show us that Hinako has now donned the mask of marriage and Shimizu Hinako can no longer be found. It’s why Junko wears a mask and why we never see her face. She’s married, and so Shimizu Junko no longer exists either. It’s also why we see Shimizu Hinako’s missing poster in Ebisugaoka during the game’s final act. She didn’t actually go missing. Shimizu Hinako has just disappeared, and in her place, we have a married woman.

The theme of female objectification is presented through the face/mask imagery, and also more obviously through the way Shu and Kotoyuki talk about her. It comes across clearest in the Fox’s Wedding ending when both men literally get into a prissy fight with each other about who Hinako belongs to. Even Shu, in all his earnestness, cannot stop himself from objectifying Hinako and selfishly attempt to hold on to his idea of who and what she should be.

Taking all of this into consideration, Hinako’s struggle becomes one of self-preservation. In her mind, marriage demands that she cuts off all ties to her friends and family. It’s why the rituals are so violent. She must literally destroy her past and parts of herself in order to become a wife, and in doing so, she loses her own identity. This is how Hinako views marriage, and in the context of the Showa Era, this doesn’t really feel too far from the truth in most cases either. If marriage will literally destroy everything that Hinako is, then what choice does she have but to fight back with equal ferocity and violence?

Adolescent Toxicity

In my view, Hinako’s friends are easily the biggest missed opportunity in Silent Hill f. There was so much potential in Shu, Rinko, and Sakuko to help reinforce the game’s themes, though that isn’t to say that what we have isn’t compelling either.

Shu: Inadvertent Objectification and Immaturity

Let’s start with Shu since we’ve already talked about him at some length. To me, Shu and Kotoyuki are two sides of the same coin. Whereas the latter takes away Hinako’s autonomy by manipulating her into marriage, Shu does the same by refusing to recognize Hinako’s femininity and literally giving her drugs in an attempt to influence her thoughts.

While Kotoyuki’s methods of manipulation may come off as extreme in Silent Hill f, I’d argue that Shu’s methods are actually way more insidious. After all, he’s presented as the Nice Guy (not a compliment, by the way) of the game and Hinako’s de facto love interest with their “will they won’t they” dynamic. Shu and Hinako’s budding romance is sweet at first, but because this is a Silent Hill game written by Ryukishi07, we’re not allowed to have nice things.

By wanting Hinako to stay as his partner, Shu himself is asserting his own idea of what Hinako should be onto her. He says he chooses not to see her as girl (even though he clearly does), which serves as a rejection of Hinako’s own feminine identity. Hinako says as much: it’s not that she hated being a girl, she just hated that being a girl meant giving up her freedom of choice.

Shu’s ultimate crime comes in the form of the Red Capsules, which serve as your primary healing item in the first playthrough. While the Red Capsules are meant to help with self-reflection, they can also be extremely dangerous. In trying to get Hinako to recognize his feelings for her and stop the wedding, Shu was willing to do so by any means necessary even if that meant causing a mental breakdown and resulting in Hinako going on a murderous rampage.

Rinko: Pride and Envy

Rinko gets a lot of flak for being the Regina George of Silent Hill f and while that take certainly isn’t wrong, I think she might be the most complex and relatable out of the three friends.

From the start, it’s clear that Rinko has a thing for Shu, who has a thing for Hinako, which makes Rinko resent Hinako. This leads to all sorts of unhinged behavior, like Rinko literally pushing Hinako down a flight of stairs and convincing Shu to leave her behind in the middle school. If we assume that most of the game’s events are actually just taking place inside Hinako’s head, I think it’s fair to argue that a lot of Rinko’s actions here are probably exaggerated, though rooted in truth. This comes through most clearly in the Dark Shrine segment where Hinako undergoes a ritual to sacrifice her friends.

Rinko’s notes and diary entries reveal that she takes pleasure in being class president because of the power and sense of superiority it gives her. It certainly helps that her family is rich, and all her acts of kindness and generosity like buying candy for her friends are just a front. She wants her friends to love her and look up to her, and she just wants to lord over them. While her villainous nature comes off as very cartoonish and on-the-nose, I’m not sure these thoughts are entirely unrealistic either. Again, I think Hinako must be exaggerating some of these traits in her head but even if she wasn’t, is it so difficult to believe that a teenager who doesn’t know any better wouldn’t revel in the cruel joy of feeling like you’re better than your peers?

The theme of women constantly being pitted against each other also comes up in Rinko’s story, particularly in her envy of Hinako and Shu’s friendship. She’s unable to see Hinako as anything but a threat despite Hinako insisting that she and Shu are just friends. In subsequent playthroughs, however, Rinko proves that she’s capable of redemption. She begins to reflect and wonder why she’s only capable of ugly thoughts, and if everyone around her has been able to see through her friendly veneer this entire time. She questions why she couldn’t just maintain her friendship with Hinako; if she’d done so, she’d be able to learn more about Shu through Hinako and perhaps their relationship might have advanced.

Rinko displays all of the insecurities and casually cruel thoughts we so often forget that teenagers are capable of. When you put someone like Rinko is an overwhelmingly patriarchal environment like this one, her worst traits only get amplified.

Sakuko: Neurodivergence in a World That’s Not Ready for It

Sakuko probably garnered the most interest and intrigue as the promo materials for Silent Hill f began to roll out. She’s always calling Hinako a traitor, which spawned interesting theories about she and Hinako forming a suicide pact and feeling betrayed because Hinako backed out of it. I would’ve loved to see that story play out, but Sakuko’s story ends up being a lot simpler: she’s neurodivergent in a world and time period that are woefully ill-equipped to deal with mental issues, and she suffers for it.

As Sakuko’s had a lot of difficulty making friends, she clings to Hinako, who promises that they’ll be together forever. So when Hinako is set to marry and leave Ebisugaoka, Sakuko sees it as a betrayal. Because of her autism, she’s unable to manage anything more nuanced than calling Hinako a traitor and she likens this betrayal to being left alone in the dark, which is one of Sakuko’s greatest fears.

Unfortunately, that’s where Sakuko’s character development arc ends. Past that, Silent Hill f doesn’t do anything particularly interesting with her as far as her friendship with Hinako goes. Instead, Sakuko is used as a plot tool to demonstrate that the strange deities of Ebisugaoka are real. In her notes, she states that two different gods have visited her in her dreams, pulling her in different directions. This is a clear reference to the fox and Tsukumogami, who fight each other via Hinako’s abilities.

Personally, I think the deity stuff is cool and I’ll never turn down a good story about fighting god. But in Silent Hill f, a game that’s so preoccupied with Asian feminism, I definitely wish Sakuko could’ve been utilized more.

Parental Neglect and Abuse

Hinako’s parents are the driving force of the story in Silent Hill f. They’re the ones who have arranged the marriage after all, and Hinako’s home life is what defines her, her actions, and her thoughts.

Silent Hill f sets up her father, Kanta, as your typical abusive father who gets violent towards his daughters and his wife. His cruelty is emphasized at the end of the first playthrough when we learn that he’s in debt, and Hinako reaches the conclusion that he’s selling her into marriage in order to pay off his debts. All of this is turned on its head when you reach the true ending, where it’s revealed that Kanta was simply a foolish, misguided man who believed that it was necessary for a man to look strong in front of his daughters.

Hinako’s mother, Kimie, reveals that Kanta had always been gentle with her when their daughters weren’t around. We even learn that Kimie was suffering from an illness and Kanta had driven himself into debt trying to find the money for her surgery. In a poignant flashback, we see Kanta earnestly apologize to Hinako for all the pain that he caused her.

Make no mistake; there are no excuses for Kanta’s actions, as Hinako is right to point out. Because of Kanta’s own traditional views, he inadvertently inflicts mental and emotional damage on Hinako, which can’t be reversed. His violence and Kimie’s passiveness lead Hinako to believe to believe that marriage means nothing but a life of subservience, and instills in her a deep-rooted fear of men and her belief that women are powerless against them.

Silent Hill f tries to wrap this up nicely by having Hinako try to forgive Kanta simply because he is her father and they are family. While I can see how this might look like an unsatisfying cop-out for western audiences, I found that it resonated deeply with me as someone who’s grown up with Asian values and customs. Rebelling against your parents and “the system” to find your own way just isn’t something that’s very widely practiced in most Asian cultures, even today. Having grown up in a Chinese family, I was constantly taught that family had to stick together no matter what. Regardless of how bad things got, family would always come back together because of their familial and blood ties.

In fact, Kanta apologizing to Hinako so genuinely is probably the one unrealistic thing about this whole affair. I’d bet good money that most Asian kids will tell you they’ve never received an apology from their parents and it’s more common than not for children to simply silently move on from an incident or even apologize for it themselves, even if they weren’t even in the wrong.

Self-Actualization

So what does it all mean? What is Silent Hill f really about? I think, at its core, Silent Hill f is a story about a young Asian girl, who’s been repressed her entire life, finally achieving true freedom and self-actualization.

The conflict at the heart of Silent Hill f is largely a metaphorical one, where Hinako’s fears of marriage and the patriarchy have come to life and threatened to consume her. In seeing the game’s multiple endings, you start to see different facets of the same story and the pressures that Hinako faces. The true ending sees her grappling with multiple things — her feelings for Shu and Kotoyuki, her desire to be alone — but ultimately, she also gets what she wants: the freedom to choose, even if it might not lead to her happiness in the end.

The true ending, titled Silence in Ebisugaoka, is both chilling and satisfying. With no one left to guide her, Hinako is left completely alone with her own thoughts. There’s a melancholy that comes with stripping away all of the systems and values that you’ve become so familiar with over the years, and a sense of trepidation and uneasiness in looking over Ebisugaoka in deathly silence, with no one to guide the town but you alone. But despite the discomfort and uncertainty, this is what Hinako and, I suspect, most people who can relate to her, wants. To live life with a clear heart and a calm mind.